Users of the LAHN website will be familiar with the project which was to research informal settlements that formed in the 1960s-80s and which are now “consolidated” (and often no longer informal having received property titles and been included in the planning grid). Originally peripheral, these neighborhoods today are located in what is the first suburban ring of development – what we refer to as the “innerburbs” or the “first suburbs”. The goal was to understand the social and physical structures of these self-help settlements, their evolution and consolidation over time, with a view to thinking about appropriate public policies of housing and community rehabilitation (rehab), given that these areas are often quite distressed after decades of intensive occupation and in-situ development. That multi-city research which began in 2009 and extended through 2016 is displayed on the LAHN website, and has recently been extended with similar studies of low-income self-help housing in Texas (colonias); São Paulo (Brazil); Guayaquil (Ecuador); and in three rural pueblos of Puebla, Mexico. While many of us hoped that the UN-Habitat III meeting in Quito in 2016 would be an inflection point in the adoption of new policies oriented towards community and dwelling rehab, regrettably, as of 2021, little policy change has been observed across our case study research sites of Latin America.

Since the LAHN’s creation many researchers, students and others have made extensive use of the datasets, methodology, publications, and analysis. In creating this new page, the goal is to make publicly available a modest number of the hundreds of images that LAHN researchers have taken or created over the years. We hope that these images may prove useful for ongoing research and student writings and theses. Provided that they are not designed for commercial purposes these images may be downloaded without charge on an “honors system” of usage: we only require you to give full acknowledgement to the LAHN website and to the creator/owner of the photograph: “Courtesy of **[photographer’s name], the Latin American Housing Network website Photo Archive, www.lahn.utexas.org.”

The photographs are organized by theme and often by city and each set of city photos may best be read alongside one of the city or thematic chapters in our 2015 volume (see publications). Each chapter of that volume is also available as a pre-publication PDF in each City Page (for those who don’t have the book). The photos are displayed as a carousel or group set of images labeled with appropriate identifying material. Once you identify a picture that you’d like to use you may download it in the following way: simply click on the image and save it on your desk top. Archiving reduces the original size of the jpeg but we hope that most photos will be adequate for your use. If you require a high quality photo for publication purposes, please contact Prof. Peter Ward (peter.ward@austin.utexas.edu). En Español >

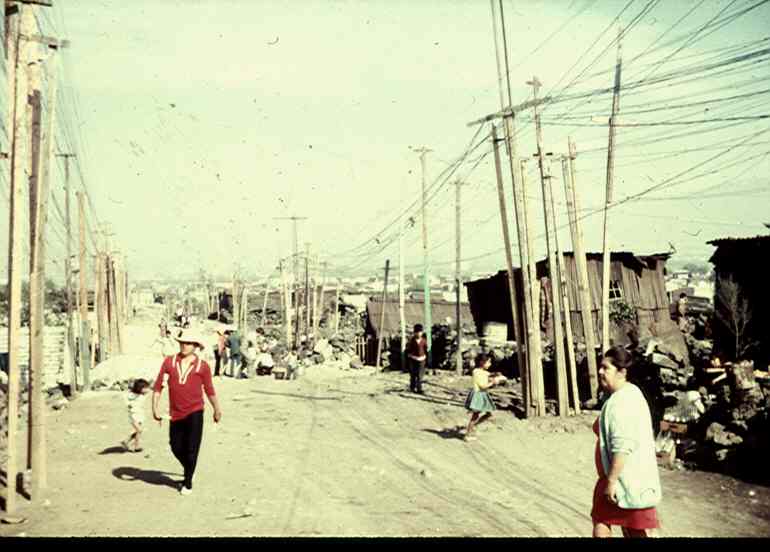

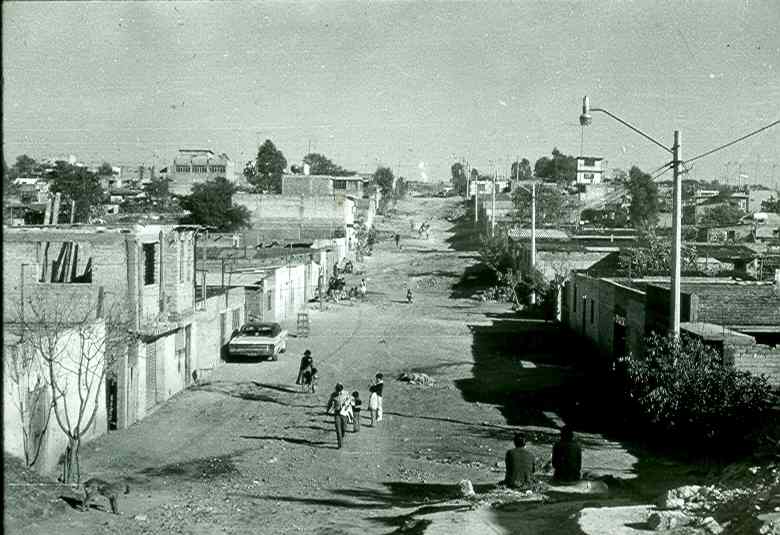

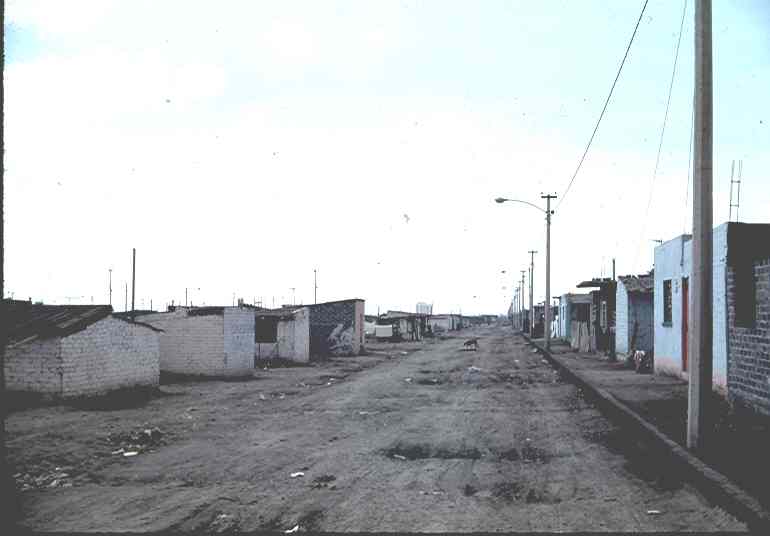

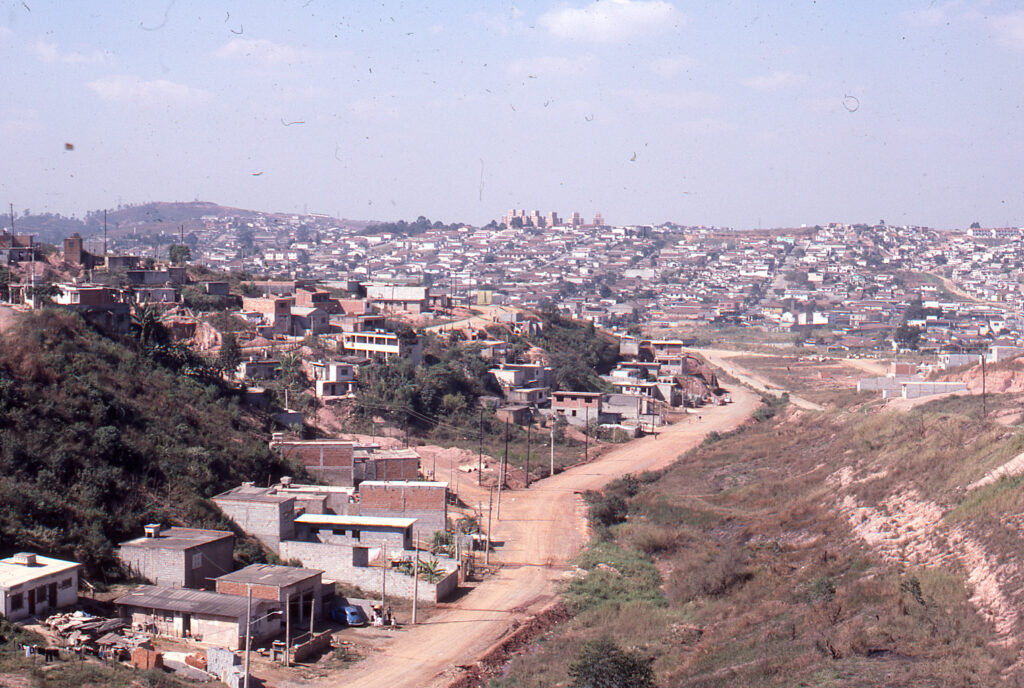

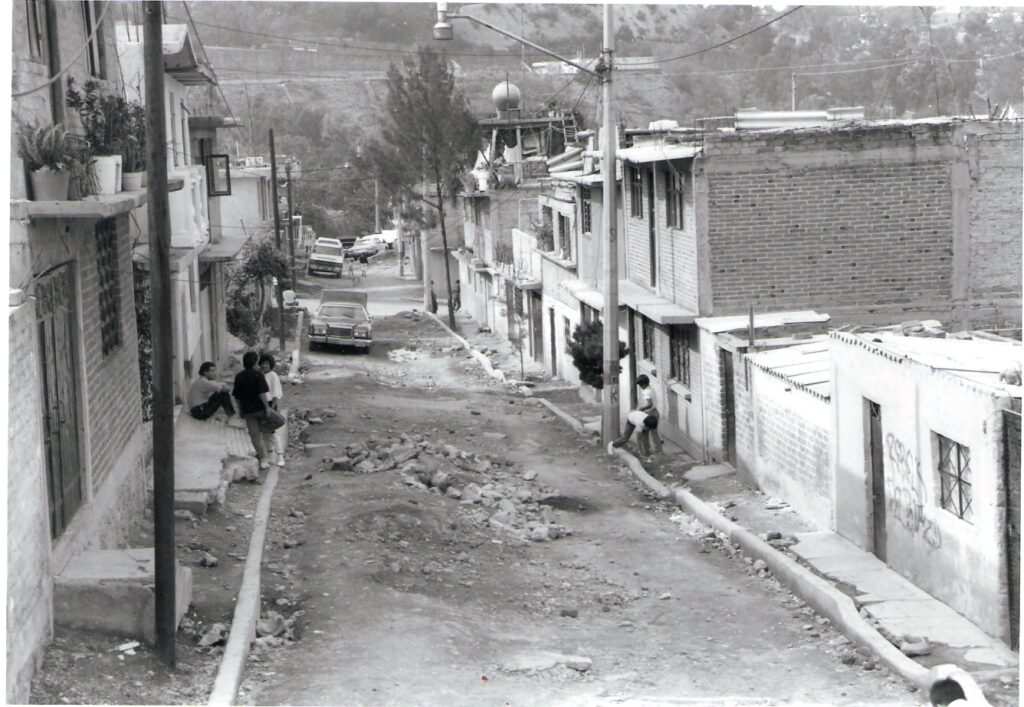

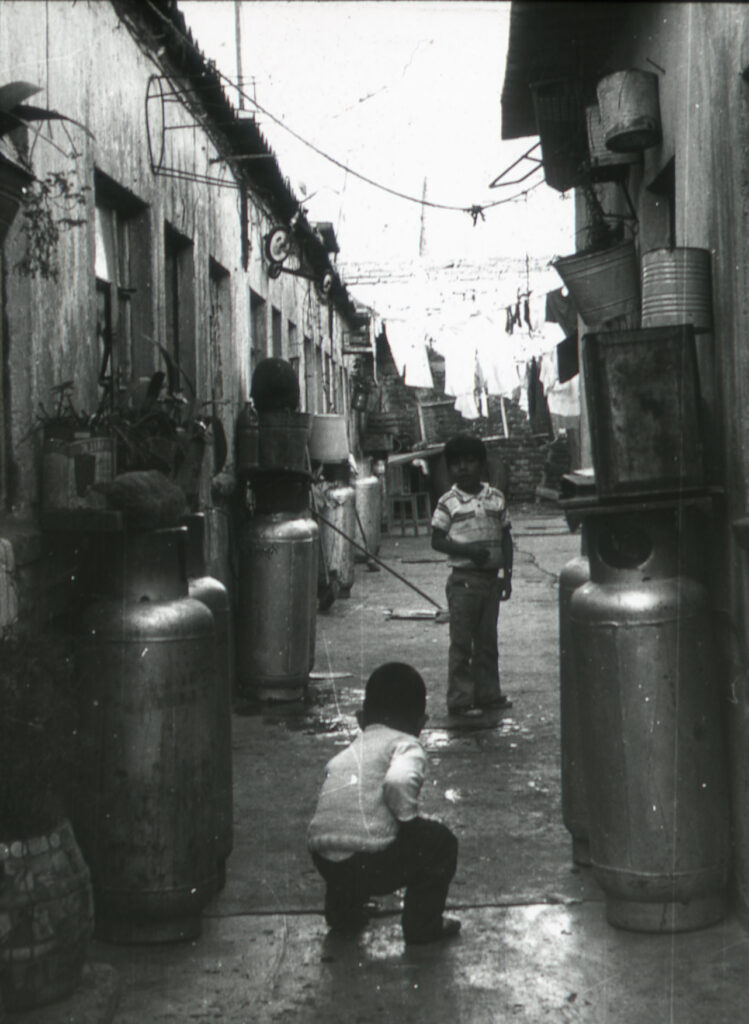

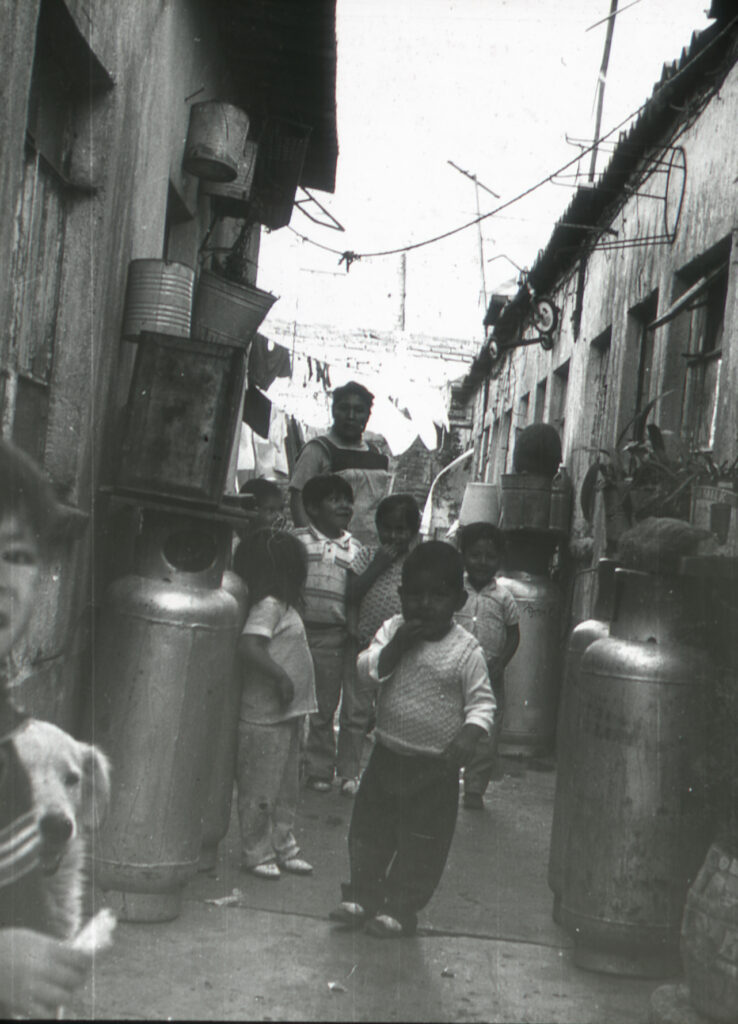

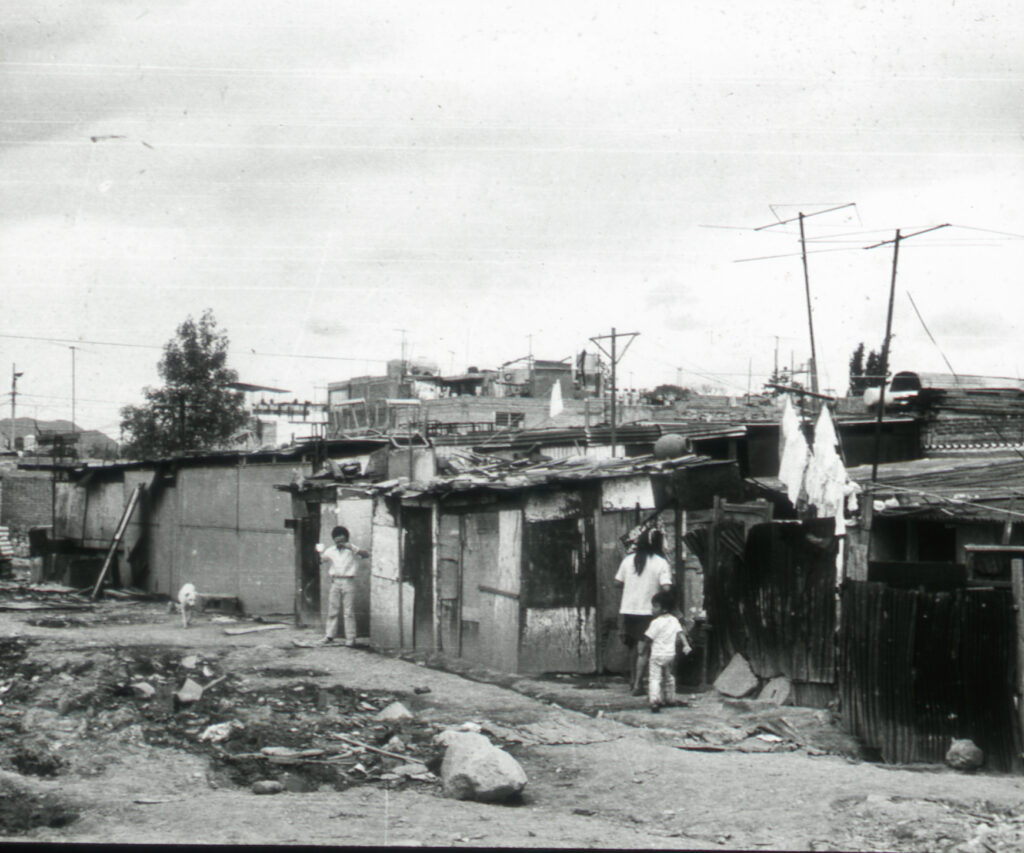

AA. Early land and informal settlements images from the 1960s-80s – Mexico City

Informal land development takes place in a variety of forms: squatting (organized invasion or accretion alongside railway lines); subdivision for sale in various forms: i) fraccionmientos clandestinos such as the developer company sales in the east of Mexico City in the 1960s; ii) private landowner sales (where formal development was frustrated often by lack of capital for infrastructure, unclear title, and/or regulations prohibiting sale); iii) sale of agricultural land by individual farmers with or without rights to sell – ejidatarios and comuneros (social property rights of holding) in Mexico; and iv) by organized invasion of land as in the cases of Santo Domingo de los Reyes and Isidro Fabela (see photos below). The phasing and extent of each type of development in Mexico has shifted with political conditions and with increased levels of planning regulation over time. From the 1990s, informal land development was less “easy” and widespread as it had been during the 1960s-80s largely due to greater planning and governmental controls. As a result, informal methods of land capture slowed, and land scarcity meant that average lot size decreased and most were considerably smaller than the modal size of 200 sq meters (10m by 20m) of yesteryear.

The following images are largely from Mexico City and were take by Peter Ward during 1970s fieldwork.

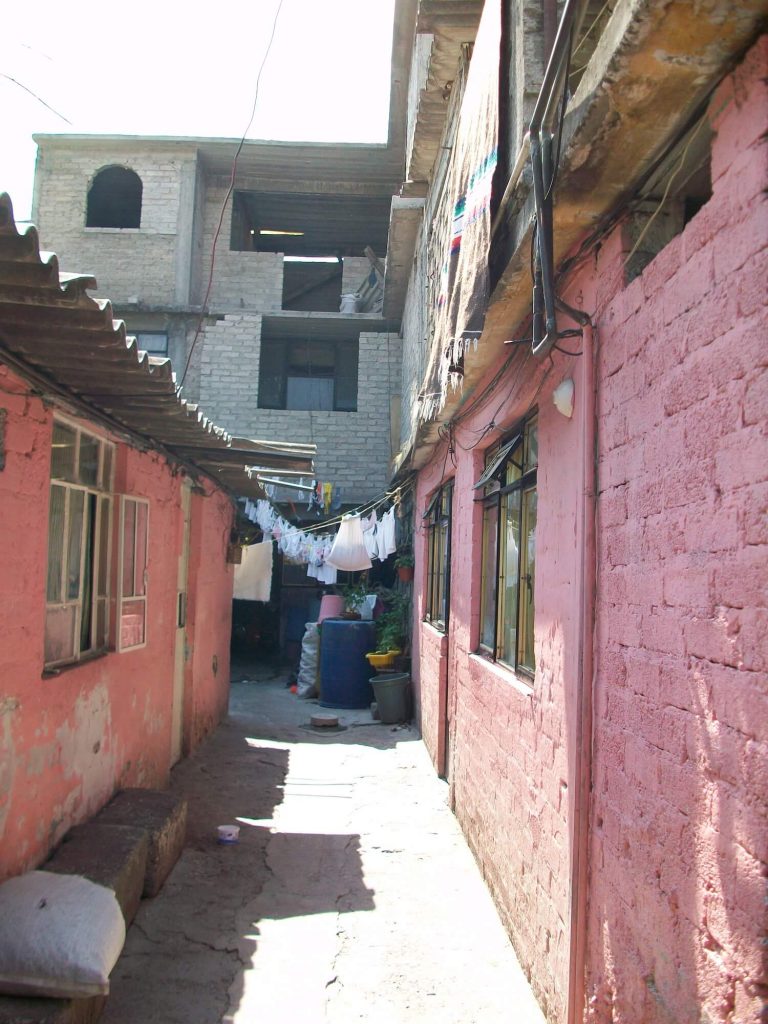

BB. Typical Contemporary Consolidated Neighborhoods – Mexico City

These are the first suburbs or “innerburbs” and were informal settlements (of various types — see slides set # AA above) that formed in the 1960s and 1970s in Mexico City and which now make up the inner ring of consolidated colonias populares usually with full infrastructure and property titles. Densities can be quite high due to family size increase and sharing with (now) adult children and their families; as well as by the creation of low-cost rental opportunities usually on separate lots (rather than subletting) — see Photo Carousel OO Below. These neighborhoods are the focus of the LAHN research, although location, nature and lot characteristics vary by city and country.

In Mexico City we did not apply the formal household survey since we had conducted detailed interviewing in six settlements in the late 1970s along with an over-sample survey in five of those same settlements in 2009 (see “Methodology” Page and “Thirty Year Restudy” [ which includes the instrument and database]). In Mexico City the “innerburbs” were those early suburban informal settlements that began in the 1960s and 1970s and form a “ring” around the historical center and the old urban and industrial areas defined as the inner urban areas (see Map “LAHN Cities Pages – Mexico City”; “Cartel”; & PDF of the Book Chapter). In addition, LAHN principals (Ward, Jiménez, and Di Virgilio (in collaboration with graduate team members from Guadalajara and Bogotá), developed a methodology for preparing intensive case studies of single households (see Publications), which we applied in several cases in order to gain further insight about key issues that had been identified in the surveys: inheritance challenges and conflicts; informal renting and sharing; particular challenges of doing rehab, etc. Vignettes of these case studies are included on the LAHN (Mexico City) Cities Page as well as on the “Databases” Page “Interesting Case Studies”. Thereafter we applied this methodology in several of the LAHN cities as well as in Texas (see “Texas Housing Database” and “Databases” Pages — “Intensive Case Studies”).

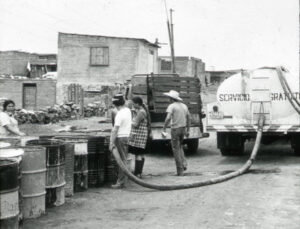

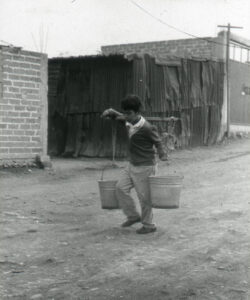

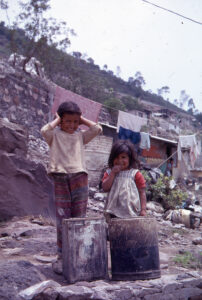

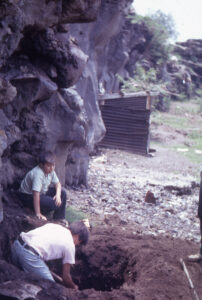

CC. Introduction of and basic services (Formal and Informal). In “Incipient” and “Early-Consolidating” Settlements (i.e. aged 3-12 years+/-)

In the early phase of settlement there are no formal services, so residents collaborate to hook up electricity, petition for water delivery trucks to fill oil drums, and for local authorities to install single standpipes in the street from which they can carry water (often work done by children — see photos). Pit latrines provide basic toilet facilities but may contaminate the groundwater. Formal electricity installation and metering generally comes first, while water and wastewater (drainage) infrastructure come much later — often after 10-15 years — once the primary and secondary service networks have been extended into previously unserviced areas. Street paving is less prioritized, except for access and principal thoroughfares.

Informal hook up to power lines — so called “diablitos” , 1974 picture. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Informal hookups to temporary power lines (Photo: Peter Ward)

Informal hook ups, Mexico City, 1974 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Santo Domingo los Reyes, 1974. (Photo: Peter Ward). Water tanker delivers "free" service to residents oil drums

Ampl. Isidro Fabela, 1974. (Photo: Peter Ward). Young children carry water from the communal tap to the home.

Ampl. Isidro Fabela, 1974. (Photo: Peter Ward). Young children carry water from the communal tap to the home.

Ampl. Isidro Fabela, 1974. (Photo: Peter Ward). Communal water spiggot communal tap to the home.Comm

Ampl. Isidro Fabela, 1974. (Photo: Peter Ward). Older children dig pit latrines.e communal tap to the home.

Sao Paulo, 1985. (Photo: Peter Ward). Primary level infrastructure extensions to the periphery.

Sao Paulo, 1985. (Photo: Peter Ward). Informal drainage off lot to adjacent open land

DD. Typical Contemporary Consolidated Neighborhoods – Guadalajara

Guadalajara Monterrey, Mexico was one of three sites that were selected for the LAHN project (along with Mexico City and Monterrey). In the case of Guadalajara the early suburban informal settlement expansion began in the 1970s and 1980s and form a “ring” around the historical center and central municipality extending into the surrounding municipalities(see Map “LAHN Cities Pages – Guadalajara; “Cartel”; & PDF of Book Chapter). The study was undertaken by faculty and students from the Universidad de Guadalajara under the direction of LAHN co-founder Dr. Edith Jiménez.. The study began with an analysis of maps displaying the socio-economic characteristics of the innerburb settlements followed by household surveys in selected neighborhoods. In Guadalajara the team worked intensively in three settlements: Echeverría; Jalisco, and Rancho Nuevo (see “settlement descriptions” on Guadalajara City Page). Redacted survey results are available on the Databases pages and in the EXCEL “Comparative Matrix”.

Colonia Jalisco, Guadalajara, 2011. (Photo: Peter Ward) External stairs linking rooms and levels in two adjacent homes

Guadalajara, 2011. (Photo: Peter Ward) Rental tenement.

Guadalajara, 2011. (Photo: Peter Ward) Sensitive policies to facilitate wheelchair access (but then obstructions on the sidewalk…)

Colonia Jalisco, Guadalajara, 2011. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guadalajara, 2011. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guadalajara, 2011. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Colonia Jalisco, Guadalajara, 2011. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Colonia Jalisco, Guadalajara, 2011. (Photo: Peter Ward). Abandoned corner lot

EE. Typical Contemporary Consolidated Neighborhoods – Monterrey, Mexico

Monterrey, Mexico was one of three sites that were selected for the LAHN project (along with Mexico City and Guadalajara). The “innerburbs” were those early suburban informal settlements that began in the 1960s and 1970s and form a “ring” around the historical center and the old urban and industrial areas defined as the inner urban areas (see Map “LAHN Cities Pages – Monterrey”; “Cartel”; & PDF of Book Chapter). The study was undertaken by graduate students and faculty from the University of Texas and from the Tec. de Monterrey (ITESM). For the Texas team it formed part of a year-long policy project class that comprised comparative data collection of innerburbs of Austin, Texas, and Monterrey. In both cities we began with an analysis of maps displaying the socio-economic characteristics of the innerburb settlements followed by household surveys in selected neighborhoods. (A full discussion of innerburbs and the Austin case is available here as a PDF.) In Monterrey we worked intensively in two settlements: Valle Santa Lucía and a smaller adjacent neighborhood of Francisco Villa (see “settlement descriptions” on Monterrey City Page). Redacted survey results are available on the Databases pages and in the “Comparative EXCEL Matrix” (selected variables only).

In addition, the ITESM and UT-Austin teams (in collaboration with team members from Guadalajara and Buenos Aires) developed a methodology for preparing intensive case studies (see Publications), which we applied in several households in order to gain further insight about key issues that had been identified in the surveys: inheritance challenges and conflicts; informal renting and sharing; particular challenges of doing rehab, etc. Vignettes and data from these case studies are included on the LAHN (Mexico City) Cities Page as well as on the “Databases” Page “Interesting Case Studies”. Thereafter we applied this methodology in several of the LAHN cities, as well as in Texas (see “Texas Housing Database” and “Databases” Pages — “Intensive Case Studies”).

Col. Valle Santa Lucía. 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Col. Valle Santa Lucía. 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Col. Valle Santa Lucía. 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Col. Fco Villa, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward) Main access road (former arroyo) with no stormwater drainage causes flooding in parts of the colonia

Col. Fco. Villa. 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward). Consolidation of a corner lot

Colonia Fco. Villa, 2009, (Photo Peter Ward). Step and panel slots (for “portcullis” insert) that provide protection from flooding,

Col. Valle Santa Lucía. 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward). External staircase

Col. Valle Santa Lucía. 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward). Conversion of former front room into garaging (with improvised gating).

Colonia Fco. Villa, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward)Steps and low wall to prevent flooding.

Boundary road to Fco. Villa Colonia, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward) Former arroyo, paved over without stormwater drainage, floods frequently.

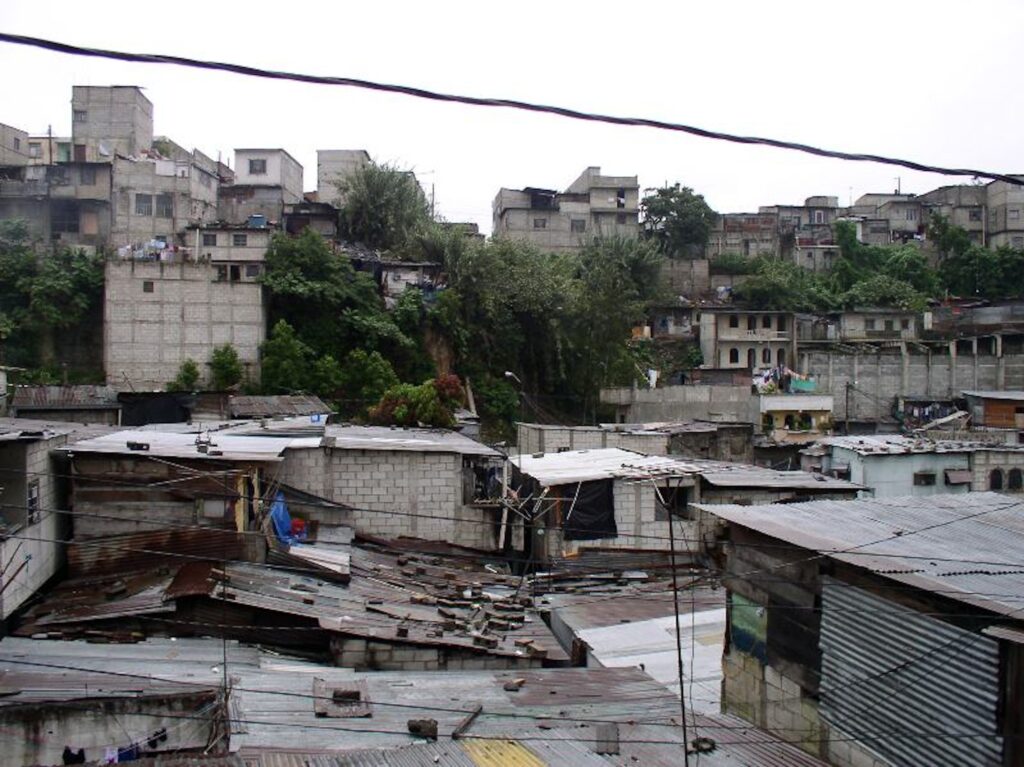

FF(i). Inner-City Consolidated Neighborhoods – El Esfuerzo (also known as La Limonada), Guatemala City

The Guatemala City case studies reflect two types of consolidated self-help settlements: the first shown here is that of an inner city former shanty town located in a barranca quite close to the city center. It grew accretively and was never planned or laid out a grid of streets and regular blocks. Thus streets are narrow, and some are little more than alleyways; lots are very small with little or no yard space which severely constrains in situ retrofitting and rehab. See Chapter 6 of the LAHN Housing book for detailed discussion by author Professor Bryan Roberts (who figures in one of the photos with the son of one of the original leaders with whom he conducted fieldwork in 1970).

El Esfuerzo main street, 1968. (Community archive photo)

Same street 2008, El Esfuerzo, (Photo: Peter Ward)

El Esfuerzo/La Limonada, (Google Earth)

Three story dwelling, main street of El Esfuerzo, (Photo: Peter Ward)

Looking across the mostly unconsolidated roofs of El Esfuerzo, 2010 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Entry main street to El Esfuerzo, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Narrow side street in El Esfuerzo, 2010, (Photo: Peter Ward)

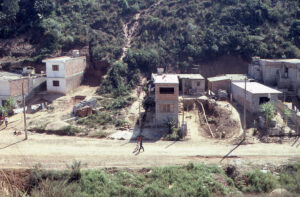

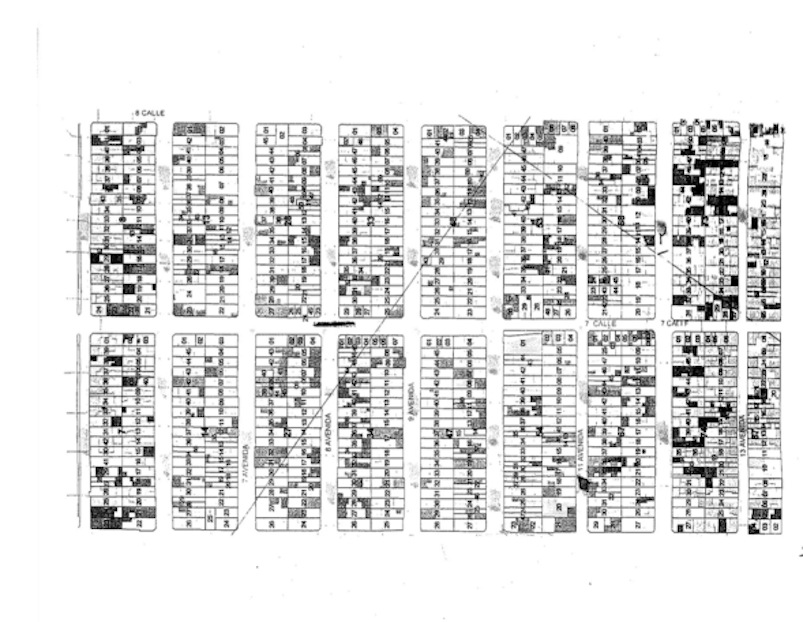

FF (ii) Suburban Consolidated Neighborhoods – La Florida, Guatemala City

The Guatemala City case studies reflect two types of consolidated self-help settlements: the second is shown here and composes are very large settlement laid out in the late 1950s. It formed in a municipality that was then adjacent to the central municipality of Guatemala City. Lots were large and deep and many have since been divided along the middle (perpendicular to the street). Homes are well consolidated, and in this case include both vertical floor additions as well as extensions to the rear (given the depth of the lot). Some renting occurs (see the handwritten sign on lot 7-71). See Chapter 6 of the LAHN Housing book for detailed discussion by author Professor Bryan Roberts.

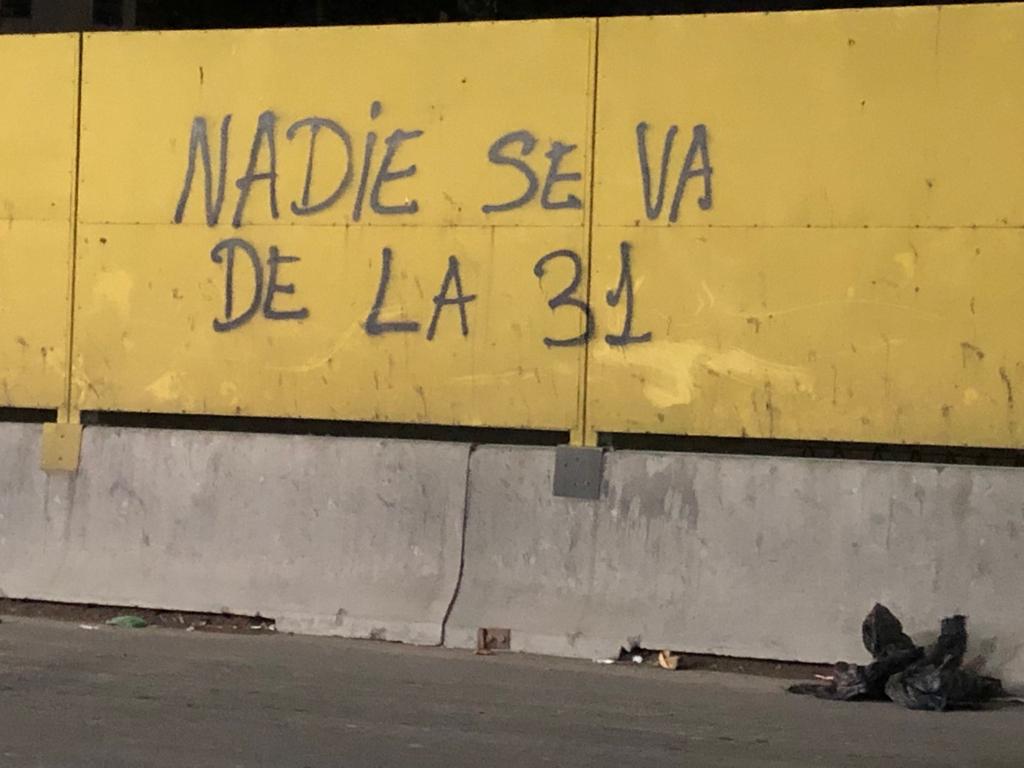

GG (i) Inner-City Consolidated Neighborhoods – Las Villas of Buenos Aires

Rather like the case of Guatemala described above, Buenos Aires has two broad types of consolidated settlements: the smaller universe of inner city and inner ring villas which comprise homes on small lots with (often) and irregular layout of streets and alleyways. The villas — sometimes called villas miserias – are often subject to threats of removal and therefore consolidation levels are mixed. Also there are major challenges for home improvement and renovation on such small lots. See the LAHN housing chapter by Mercedes Di Virgilio for detailed account of the Buenos Aires case.

The more recent photos taken by Dr. Mercedes Di Virgilio do show that there has been a major commitment to barrio improvements and infrastructure in recent years — although, as she notes, there is still some internal variation in consolidation levels.

Fotos barrios Inta. Tomadas en el año 2010 y 2015. Producción de las fotos: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio | Dra, Mariana Marcos | Dra. Gabriela Mera. Las fotos reflejan el proceso de urbanización que se llevó a cabo en el barrio (vease las fotos de 2015). Se aprecia la consolidación de las fachadas y la denominación oficial de las calles. También algunos contrastes que aún persisten.

Fotos Barrio 31. Tomadas en el año 2019. Las fotos reflejan el proceso de urbanización que actualmente se lleva a cabo en el barrio. Producción de las fotos: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio. (Vease la foto de 2008 tomado por Peter Ward)

Barrio Inta, 2010. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio)

Barrio Inta, 2010. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio)

Barrio Inta, 2015. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio and colleagues)

Barrio Inta, 2015. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio and colleagues)

Barrio Inta, 2015. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio and colleagues)

Barrio Inta, 2015. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio and colleagues)

Barrio Inta, 2015. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio and colleagues)

Villa 31, 2008. Close to the center of Buenos Aires. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Barrio (Villa) 31, 2019. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio)

Barrio (Villa) 31, 2019. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio) “No-one is leaving the 31”

Barrio (Villa) 31, 2019. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio)

Barrio (Villa) 31, 2019. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio)

Barrio (Villa) 31, 2019. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio)

Narrow backstreet in Villa Tranquila, Municipio de Avellaneda, 2009. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Villa Tranquila, Section of social interest housing production, 2009. (Photo: Dra. María Mercedes Di Virgilio)

GG (ii) Suburban Consolidated Neighborhoods – Loteos Populares, Buenos Aires

The second type are the loteos populares or asentamientos. Although less widely documented and discussed compared to the villas, this is the larger universe of consolidating and consolidated informal settlements. Usually subdivided to a plan and lots sold off to would-be residents the loteos are located in the intermediate and peripheral rings of the city. Loteos were generally developed as low cost subdivisions for self-building. Asentamientos were invasions (like Villas), the primary difference being that they were more peropheral and were laid out in a more regular block form. Lots are larger and allow for horizontal expansion such that second stories are less common than in many LAHN cities. See the LAHN housing chapter by Mercedes Di Virgilio for detailed account of the Buenos Aires case. Also compare the differences on the EXCEL data sheets (Databases pages).

Although not one of the LAHN cities, several photos of consolidated asentamiento from the city of Neuquen are also shown below.

“Asentamiento” at early stage of development (2009) , Municipality Almirante Brown. (Photo: Peter Ward)

“Asentamiento” at early stage of development (2009) , Municipality Almirante Brown. (Photo: Peter Ward)

San Mateo, 2008. (Photo: Peter Ward)

San Mateo, 2008. (Photo:Peter Ward)

San Jorge. Asentamiento regularizado (2010)

San Jorge. Asentamiento regularizado (2010)

Additional images from Neuquen.

Neuquen (Photo: Peter Ward)

Neuquen (Photo: Peter Ward)

“Toma” Monte Sinay, Nuequen. (Photo: Peter Ward) Toma is an invasion.

HH(i) Inner City Consolidated Neighborhoods – Favelas of Brazil

While favelas are well known and widely described, they are, in fact, a smaller self help universe that loteamentos which correspond more broadly to the innerburb informal subdivisions described for the other LAHN cities. Among the LAHN cities we see favelas as similar to the Villas (Buenos Aires) and to small inner-city shantytowns that one occasionally finds in other cities (see for example the Guatemala case study settlement of El Esfuerzo). Their location and visibility often makes them especially susceptible to eradication programs, although in Brazil especially they are subject to upgrading schemes such as the favela bairro propgram. The main differences are that favelas are more likely to be in the inner city of closer to the city center than loteamentos and barrios/colonias populares; their layout is less regular; lots are much smaller; densities are higher; renting is common (see images). While consolidated, these characteristics make for much greater challenges when it comes to policies of in-situ housing and community rehab which is why we have made the distinction here and in the 2015 Housing Policy volume.

Classic Favela. Cantagalo-Pavão-Pavãozinho, Rio de Janeiro. (Photo: Kristine Stiphany)

Classic favela, Brasilândia, São Paulo, 2012. (Photo: Kristine Stiphany)

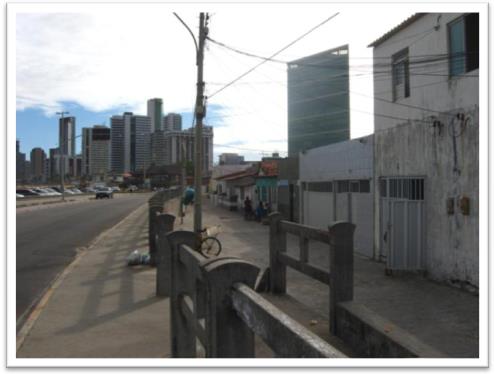

HH (ii) Suburban Consolidated Neighborhoods – Lotementos and Favelas, Brazil

While favelas are well known and widely described, they are, in fact, a smaller self help universe that loteamentos which correspond more broadly to the innerburb informal subdivisions described for the other LAHN cities. Brazil has had a long history of upgrading interventions in both favelas (favela bairro program), but in major cities such as São Paulo different public policy interventions have often been undertaken in a single settlement (or adjacent settlements) over time. Thus one sees different origin informal settlements with sites and servicing projects, upgrading programs, and conjuntos all in a single settlement representing different phases of policy intervention. For further details see the São Paulo Extension pages on the LAHN website.

Consolidating loteamento, 1985. São Paulo, (Photo Peter Ward)

Consolidating loteamento, 1985. São Paulo, (Photo Peter Ward)

Loteamento, São Paulo. (Photo Kristine Stiphany)

Sites and services project, São Paulo. (Photo: Kristine Stiphany)

Consolidated Sites and services project, São Paulo. (Photo: Kristine Stiphany, 2012)

Conjunto, Cidade Tiradentes, São Paulo. (Photo: Kristine Stiphany)

Conjunto, Heliopolis, São Paulo. (Photo: Kristine Stiphany)

Coronel Fabriciano, Recife, 2010 (Rua 18 de noviembre). (Photo: Flavio de Souza)

Brasila Teimosa, Recife, 2010 (View looking back towards the center). (Photo: Flavio de Souza)

Vila Aliança, Recife, 2010. (Photo Flavio de Souza)

Avenida Brasilia Formosa, Recife 2010. (Brasilia Teimosa is on the left). (Photo: Flavio de Souza)

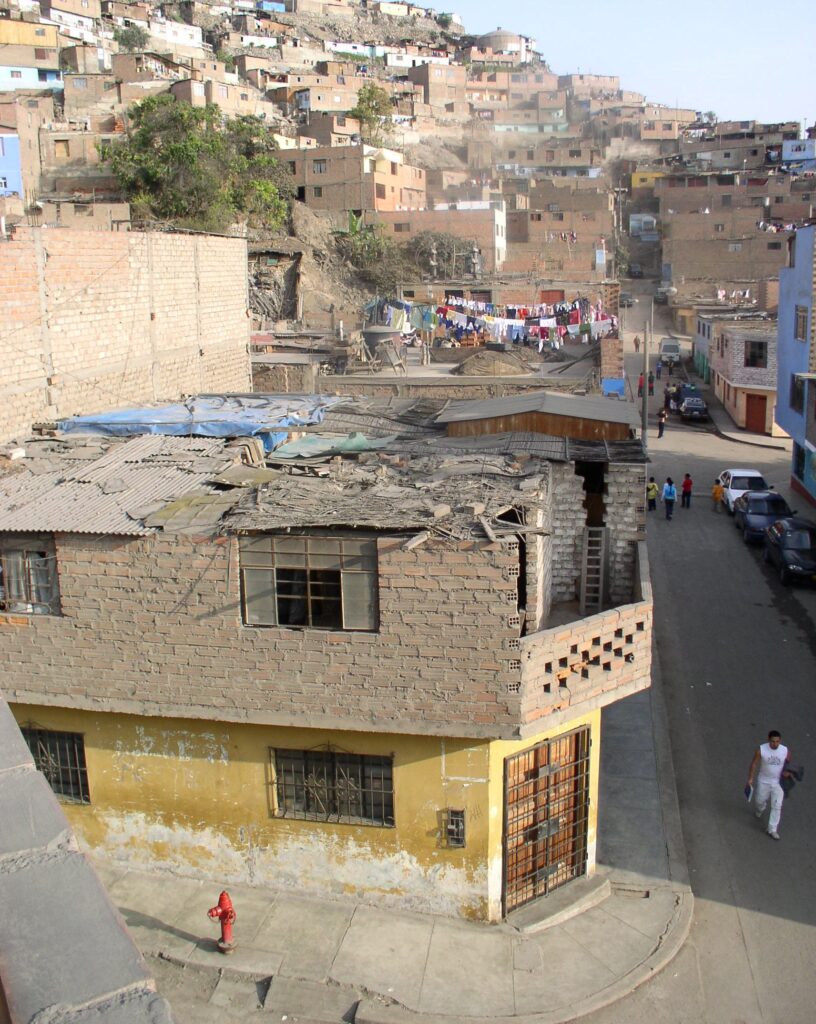

II. Suburban Consolidated Neighborhoods – Pueblos Jóvenes, Lima

Some of the earliest research about squatter settlements emerged from the Lima case in the 1960s and early 1970s. Usually comprising invasions of desert land with lots laid out and provisional dwellings of straw matting (see first Photo [below] for a recent example), homes were gradually “consolidated” in the classic gradual process of self-building (see PDF of Chapter on the Lima City Page). originally called “barriadas“, in the 1970s the less derogatory and more positive term of puebos jóvenes became more widely adopted.

In Lima the “innerburbs” were those early suburban informal settlements that began in the 1960s and 1970s and because of the topography development has formed three “cones” — South, East and North — along three valleys out from the city center (see Map “LAHN Cities Pages – Lima; “Cartel”; & PDF of Book Chapter). The fieldwork and household survey was undertaken primarily by Danielle Rojas (UT graduate student) with collaboration from Olga Peek (University of Leuven). The study began with an analysis of maps displaying the socio-economic characteristics of the innerburb settlements (undertaken by the larger Lima team [see personnel on the Lima page]), followed by household surveys in selected neighborhoods. In Lima the team worked intensively in three settlements: Independencia, Alfonso Ugarte and 23 de May (see “settlement selection” protocols on the Lima City Page). Redacted survey results are available on the Databases pages and in the “Comparative EXCEL Matrix.

In addition, as part of her (then) Masters degree, Olga Peek was using an intensive case study methodology to document the build-out consolidation process of households and vignettes of ten case studies are included on the LAHN (Lima) Cities Page as well as on the “Databases” Page “Interesting Case Studies”. Several of these build-out examples are included in the book PDF.

Pachacutec, 2009. (Photo: Peter Ward) A recently formed pueblo joven in the North sector of Lima

Independencia, 2008. (Photo: Peter Ward). Part of the LAHN team

Independencia, 2008. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Independencia, 2008. (Photo: Peter Ward).

23 de Mayo, 2012) (Photo: Danielle Rojas)

Alfonso Ugarte. (Photo: Danielle Rojas) Local store and room for rent

“Gated street” in consolidated pueblo joven, Lima. (Photo: Danielle Rojas)

JJ. Typical Contemporary Consolidated Neighborhoods – Santiago de Chile

In Santiago consolidated self-help settlements are rather different than elsewhere. In the post-coup Pinochet era of the 1970s and 1980s Chile undertook aggressive policies to evict settlers in informal settlements that had emerged in the 1960s under Frei and then under Allende. Thus most tomas (invasions) were eradicated. some were moved to social housing which comprised a single core dwelling and these were often added to by the residents through extensions or a second floor. Some settlements did survive (El Bosque is one such), but many neighborhoods show some conformity of core unit and then improvised extensions. Few units have a concrete roof which would allow additional floors to be added, and where they exist, the second floor is a wooden structure built up from the first floor wooden frame.

El Bosque, Santiago, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward)

El Bosque, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward)

El Bosque, Santiago, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward)

El Bosque, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward)

El Bosque, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Santiago, 2008. (Photo: Peter Ward) Gated Street in a consolidated settlement.

La Union, Santiago, (Photo: Carolina Flores)

El Bosque, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward)

La Union, Santiago, (Photo: Carolina Flores)

KK. Typical Contemporary Consolidated Neighborhoods – Montevideo

Two rather different consolidated settlements that appear in the LAHN study and which are described by Marsiglia and Doyenart in Chapter 10 of the 2015 volume. Both are fairly typical of barrios in Montevideo and both formed through invasion in the 1970s. Casabó appears to be the more consolidated, while 19 de abril‘s growth has been more accretive over time. In another settlement (Maracaná) the blocks were so large that lots formed first around the edges (as is usual), and then vacant land in the center of the block was accessed by L shaped access roads (see image). These interior access roads are sometimes narrow and the sharp interior right angle turns makes it difficult for large vehicles (garbage trucks, fire fighter trucks, etc.) to enter.

Maracaná barrio, 2010 (Photo Peter Ward) Access road to center of the block,

19 de abril, barrio, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward)

19 de abril barrio, typical street with partial stormwater drainage (Photo: Peter Ward)

Casabó barrio, 2011, (Photo:Peter Ward)

Casabó barrio, informal self building (Peter Ward)

Two story house, 19 de abril, (Photo Peter Ward)

19 de abril barrio, (Photo: Peter Ward). Neighboring low-level consolodated dwellings

LL. Typical Contemporary Consolidated Neighborhoods – Bogotá

The topography of Bogotá does not make for “rings” of suburban development but the chapter by Angelica Camargo Sierra describes the development of the barrios along the axis of the valley as well as out into the surrounding municipality of Soacha. Several of these settlements were studied by Alan Gilbert and Peter Ward as part of their major three country study in the late 1970s (Housing, the state and the poor, published by Cambridge University Press in 1985 and reissued in digital format in 2009). Barrios were formed as “pirate settlements” (barrios piratas) through private informal lot sales by the land owners who were often farmers.

1979 Casablanca barrio. (Photo: Alan Gilbert)

2009 Casablanca barrio. (Photo: Peter Ward)

2009 Casablanca barrio. (Photo: Peter Ward)

2009 Casablanca barrio. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Atenas Barrio, 2009. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Atenas Barrio, 2009. (Photo: Peter Ward)

MM. Contemporary Consolidated Neighborhoods – Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

These photos come from two major studies undertaken at UT-Austin. The photos from Colonia Cristo Rey are by D. Erika Grajeda who was a member of the LAHN team. Cristo Rey is one of the largest consolidated barrios of San Domingo. The photos from a less consolidated settlements of Los Platanitos are by graduate student members of the Community and Regional Planning Department’s ongoing program of collaborative research with members of the community (2008-19) directed by Dr. Bjorn Sletto (see the Cañada project= at https://sites.utexas.edu/santodomingo-informality)

Barrio Cristo Rey: Narrow Side Street (Photo Dr. Erica Grajeda)

Barrio Cristo Rey: Access alleyway. (Photo Dr. Erica Grajeda)

Barrio Cristo Rey: Side Street (Photo Dr. Erica Grajeda)

Barrio Christo Rey: Narrow Side Street (Photo Dr. Erica Grajeda)

Barrio Cristo Rey: Narrow Side Street (Photo Dr. Erica Grajeda)

Los Platanitos, 2018. (Photo: Juan Tiney Chirix)

NN. Common Examples of (Now) Distressed Dwelling and Infrastructure Challenges for Contemporary Policy Making

One of the important goals of the LAHN Project was to figure out the physical housing and community infrastructure policies to meet the challenge that many of these consolidated settlements faced after intensive use by residents over 20-40 years.. In the following slides we highlight some of the common on-lot challenges (deteriorated ceilings; inadequate toilet and bathroom facilities; periodic flooding; dangerous unprotected balconies; hazardous wiring; access to upper floors; dangerous staircases; etc.). At the neighborhood level one also observes challenges of broken drainage; unhealthy markets, poor playgrounds; abandonment and drug and gang havens.

Colonia Isidro Fabela, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward). Multi-household consolidated dwelling with new home in rear of the lot.

Colonia Isidro Fabela, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Colonia Isidro Fabela, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Colonia Isidro Fabela, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Colonia Pancho Villa, Monterrey.Isidro Fabela, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Colonia Santa Lucía Monterrey. 2009. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Colonia Santa Lucía Monterrey. 2009. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Guadalajara. 2009. (Photo: Peter Ward).

Colonia Santa Lucía Monterrey. 2009. (Photo: Peter Ward). “Pregnant” gate on garage to accommodate the car[

Isidro Fabela, Mexico City. (Photo: Peter Ward) Top floor of a rental lot

Colonia Jalisco, Abandoned dwelling in Guadalajara (Photo: Peter Ward)

Barrio Atenas, Bogotá, 2009 (Photo: Peter Ward) Note the broken street paving

Isidro Fabela, 2010. (Photo: Edith Jiménez) Leaking roof seeping through sealant

Valle Santa Lucía, Monterrey, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward) Dangerous balcony and cracks in real (boundary) wall

Isidro Fabela, 2010. (Photo: Edith Jiménez) Dangerous stairway to second floor of a rental structure

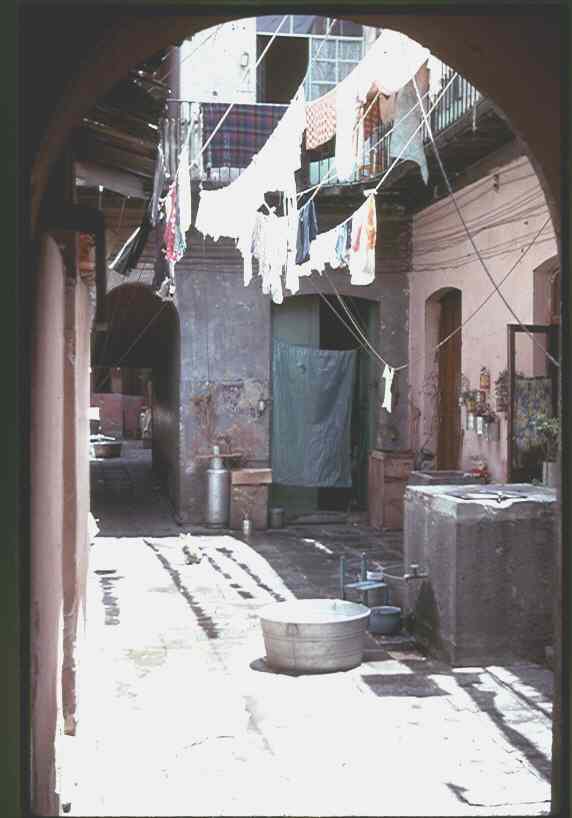

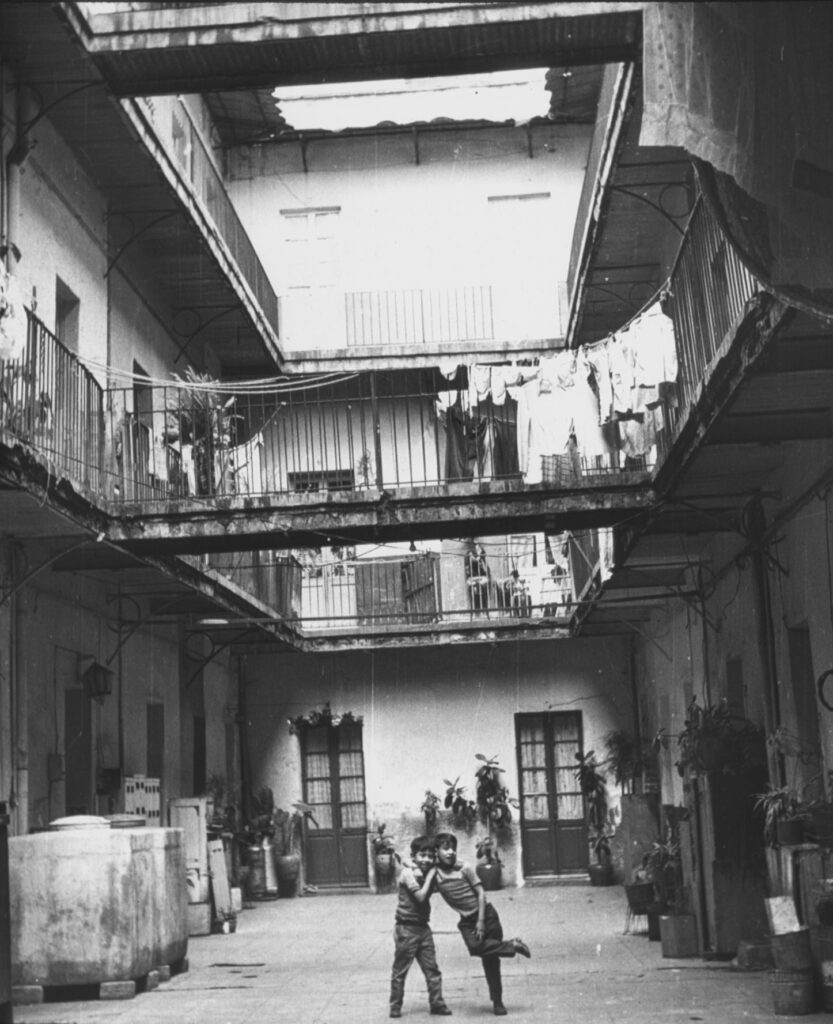

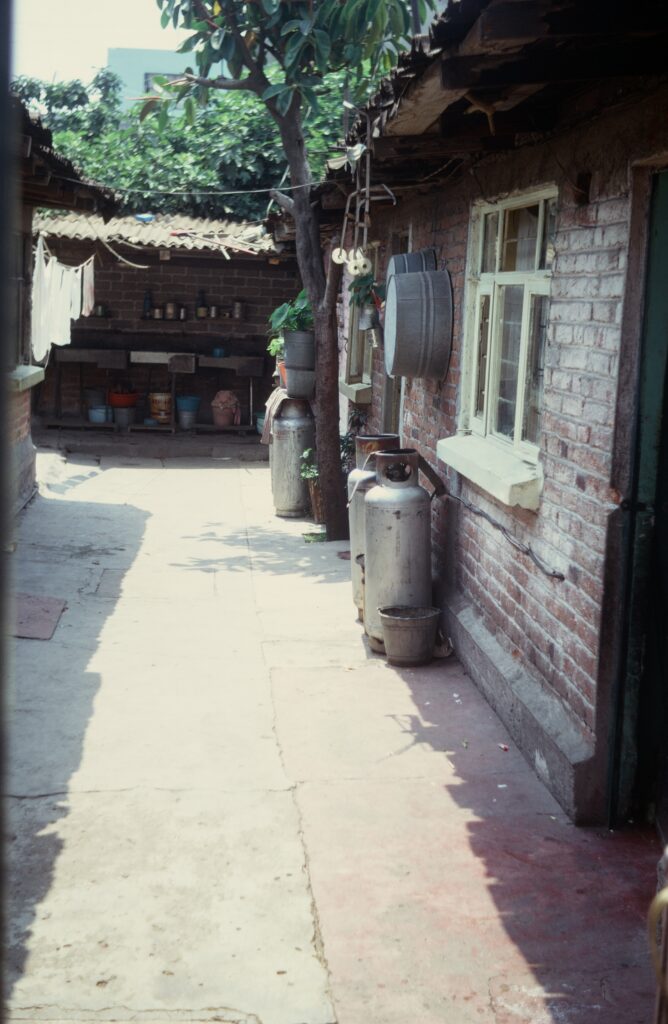

OO. Rental Tenements in Mexico City – Vecindades (Classic and New)

Many migrants to Latin American cities in the 1950s through 1970s settled first in the inner city where they had relatively easy access to unskilled employment opportunities, and low cost rentals. Such tenements have different names in different countries, but in Mexico they are called vecindades and comprised old colonial palaces or purpose built tenements that were subdivided into single room dwellings (often 15-40 households) with services shared in the patio. As the central tenements became heavily congested and supply dwindled, “new” (smaller) tenements of 5-10 households located in the colonias populares that formed in the 1960s and 1970s and which were then in process of consolidation (today the consolidated settlements that form the focus of the LAHN study). An additional type of renting were in shackyards in and around the city center and along railway lines — called “lost cities” (ciudades perdidas) in Mexico City. The latter were the prime focus of evictions during the 1970s.

Classic vecindad (tenement) in an old inner city mansion. 1973. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Shared water and washing facilities in interior patio of a classic vecindad (tenement). 1973. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Street view of a 19 century tenement building. 1974. Mexico City. (Photo: Peter Ward)

1920s purpose built vecindad in Mexico City. (Photo 1973: Peter Ward)

Inner courtyard of a classic vecinded in Mexico City. 1973 (Photo: Peter Ward)to

“New vecindad in a colonia popular of Mexico City. 1973. (Photo Peter Ward). Pairs of tanks indicate a single residence. Shared services at the end of the patio.

“Lavaderas” (washing sinks) in a “new” vecindad of a colonia popular, Mexico City. 1973. (Photo: Peter Ward)

New vecindad in a colonia popular (Isidro Fabela), Mexico City 1973. (Photo Peter Ward)

New vecindad in a colonia popular (Isidro Fabela), Mexico City 1973. (Photo Peter Ward)

“Ciudad perdida” (“lost city”

shantytown) Ixtacalco, Mexico City 1973. (Photo: Peter Ward)

PP. Examples of Rental Housing Infill in Consolidated Settlements, Latin America

Renting has always been commonplace in Latin America (see previous set of slides), and while the dominant tenure in the first half of the twentieth century, it was eclipsed as the majority form of tenure as informal settlement expanded to form the consolidated settlements of today. Within those settlements, however, there has been a rise of renting as lots are turned over to renting or rooms are offered for rent in petty-landlord tenant arrangements. Generally low quality, there is some “pocket” gentrification as lots are turned over to middle income apartments.

Guadalajara Renting in Colonia *, 2011. (Photo Edith Jiménez)

Isidro Fabela Rental, 2010. (Photo: Peter Ward) Home to 5 households.

Guadalajara Renting in Colonia **, 2011. (Photo Edith Jiménez)

Guadalajara Renting in Colonia, 2011. (Photo Edith Jiménez)

Bogotá, 2009. Rental. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guadalajara Renting in Colonia **, 2011. (Photo Edith Jiménez)

Cortiço tenements in São Paulo. (Photo: Kristine Stiphany)

Guadalajara Renting in Colonia **, 2011. (Photo Peter Ward)

QQ. Multi-household Sharing in Consolidated Settlements, Latin America

One of the fascinating and most innovative elements of the LAHN study was to begin to better understand the emergence of second and even third generation households born to the original “pioneer” self-builders who occupied land informally in the 1960s-80s. Those young families were raised in the barrio and as adults faced different housing market options often choosing to stay close by and rent (Carousel OO). Other adult children often chose to remain living with their parents (either in separate rooms or taking over another floor [see Lima example], or by building a room or small home elsewhere in the lot). Our data suggest that, unlike renting, sharing with kinsmen (especially parents) often becomes a long term option that offers not only the use value of secure residence for the second generation household but, as time goes on and the parents age and pass away, the now (quite valuable) property in exchange value terms de facto becomes part of the inheritance to the siblings, and the housing trajectory of some members. How that inheritance works can become messy (see Publications, 2011, “Second Generation Inheritance. The House that Mum and Dad Built).

Sharing can take many forms, but it is an important element when considering housing rehab to recast the parental dwelling to meet the needs of two or more households, especially if tenure has become “clouded” by inheritance conflicts between siblings.

Colonia Jalisco, External staircase to second floor (Guadalajara. Photo Peter Ward)

Colonia Jalisco, Second to third floor and adjacent house external staircase (Guadalajara. Photo Peter Ward)

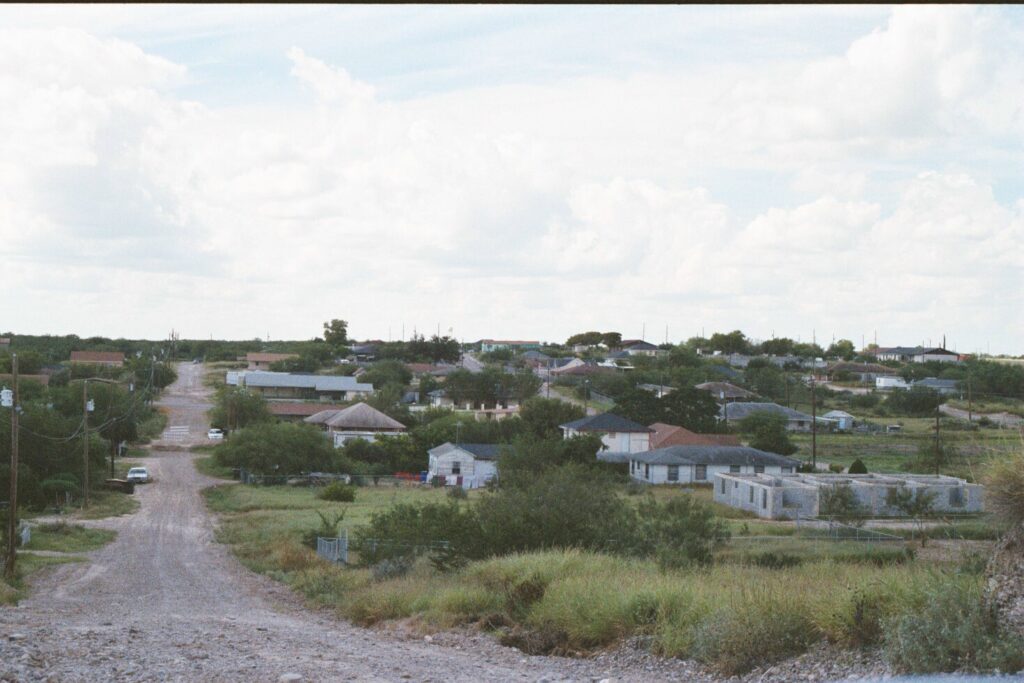

RR (i). Texas Colonias from the Border Region (See Texas Housing Studies – Extension)

While not widely studied until relatively recently self-building or self-management of housing is also quite widespread in the USA, especially (but not exclusively) along the US-Mexico border in Texas. Unlike the LAHN cities where informal land captures are by invasion or illegal land sales, in Texas un-serviced land is sold by developers under a Contract for Deed arrangement (or at least that was widely the case until the mid 1990s when state legislation required more formal contracting and basic services to be provided from the outset). But as for Latin American low- income households colonias offered a foothold on the home ownership trajectory through self-building one’s home gradually, or by placing a manufactured home (trailer) or modular home on site, gradually extending or modifying the core shell house over time. In the border region over 90% of colonia residents are Hispanic (Mexican origin), many of whom are familiar with self-building from nearby Mexico. Examples, detailed analysis, household survey databases, and intensive case studies may all be found in the “Texas Housing Database” pages.

Rio Bravo Colonia, Webb County. (Photo: Google Earth)

El Cenizo Colonia, Webb County. (Photo: Peter Ward)X

Colonia home in Valverde County (camper and shack). (Photo Peter Ward)Camper

B&E (Blas & Elias) Colonia self-built dwelling around a modular core. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Cameron Park Colonia. Self-built dwelling and modular core (Photo: Peter Ward)

Trailer home in border colonia. (Photo Peter Ward)

Owner making final adjustments to roof supports. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Side view of the same house (Note the original room at the rear now partially integrated into the roofed brick built home (Photo: Peter Ward)

Shared lot. Parents live up the hill (rear) and daughter and family in the pink house. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Melded structures: Singlewide trailer and self-built addition. (Photo: Peter Ward)

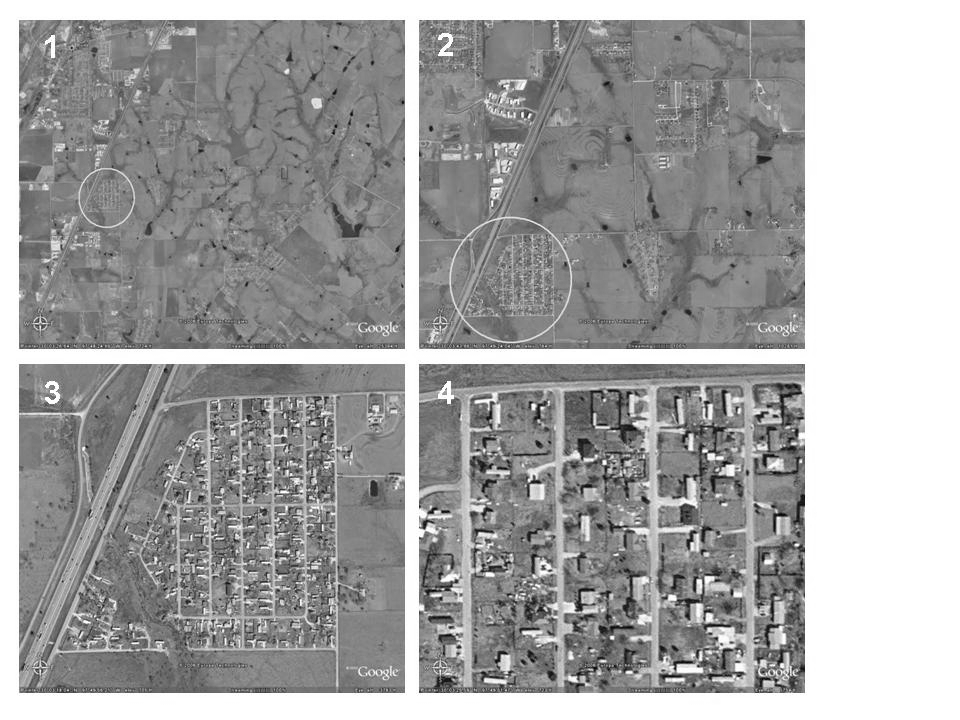

RR (ii) Informal Homestead Subdivisions (AKA Colonias but Not Along the Border) See Texas Housing Studies – Extension)

Even less well studied are self-building or self-management of housing development outside of the border region into the heart of Texas and beyond. Indeed, recent work is showing that such housing is quite commonplace outside of city limits across many parts of the USA, although the data suggest that they are slightly better off than their border counterparts (but still low-income) are communities are more ethnically mixed although Hispanics remain the majority. Dwellings are more likely to be manufactured homes and modular units rather than self-built from scratch, but there is a lot of self-building extensions, additions, and interior DIY (Do It Yourself). Infrastructure is poor and is provided by the County and by individual hook ups with private providers.

Residents would not see them selves as living in a colonia (as along the border) which is why we use the term “Informal Homestead Subdivisions” (IfHS) since that is what they are. Examples, detailed analysis, household survey databases, and intensive case studies may be found in the Texas Housing Database Pages.

Hillside Terrace IfHS alongside HI 35 (Hays County, Texas) South of Austin (Photo: Google Earth)

IfHS in Bastrop County (15 miles from Austin) (Photo: Peter Ward)

Stony Point IfHS, Bastrop County. Hybrid camper and selfbuilt home. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Rancho Vista IfHS (Guadalupe County). Two homes/households sharing a lot (single family). Photo: Peter Ward)

Hillside Terrace IfHS. Hays County (Photo: Peter Ward)

Hillside Terrace IfHS. Hays County, Texas. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Singlewide manufactured home and self-built porch extension. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Rancho Vista IfHS. (Guadalupe County, close to San Marcos). Modular home. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Rancho Vista (Guadalupe County), 2010.. Dilapidated dwelling. (Photo: Peter Ward)

False roof to provide shade over singelwide manfactured home. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Self help in Hillside Terrace, (Hays Country), South of Austin,2004. (Photo: Peter Ward)

Doublewide manufactured home placed on sitehelp (Photo: Peter Ward)

IfHS in Pima County (outside Tucson), Arizona, 2004. (Photo: Peter Ward)

IfHS in Pima County (outside Tucson), Arizona, 2004. (Photo: Peter Ward)

IfHS in in Pima County (outside Tucson), Arizona, 2004. (Photo: Peter Ward)

SS. Consolidated Barrios / Colonias in Quito & Guayaquil

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Guayaquil, 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Saldana barrio, Quito. 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Saldana barrio, Quito. 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Saldana barrio, Quito. 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Saldana barrio, Quito. 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

Saldana barrio, Quito. 2015 (Photo: Peter Ward)

TT. (Mass) Social Interest Housing Developments, 1995-2012.

From the mid 1990s onwards a number of countries began to develop mass “social” interest housing esstates on low cost peripheral and peri-urban lands. These “cookie-cutter” housing subdivisions were usually provately produced with financing support from the Federal Government. By the early 2000s it was obvious that many were plagued by problems of lack of social infrastructure, distant locations from job locations (several hours daily commute) and from previous barrios of residence, poor (low quality) construction and design, and often lack of affordability. By 2010 these problems were leading to vacant (unsold housing) and abandonment of a significant proportion of dwellings. This housing type was never the focus of the LAHN study since it was commercially produced, and was not part of the selfbuilding housing developments of the 1970s and 1980s (i.e. consolidated settlements”). That said, one can occasionally observe some self building extensions and remodelling undertaken by some residents — usually to individualize their dwelling unit (given the uniformity of design types), and to overcome some of the constructional and design inadquacies.

Mass social interest housing estate, Guadalajara. (Photo: Dr. Chen Yu)

Abandoned housing in mass social interest housing estate, Guadalajara. (Photo: Dr. Chen Yu)

Abandoned housing in mass social interest housing estate, Guadalajara. (Photo: Dr. Chen Yu)

Abandoned housing in mass social interest housing estate, Guadalajara. (Photo: Dr. Chen Yu)

Abandoned housing in mass social interest housing estate, Guadalajara. (Photo: Dr. Chen Yu)